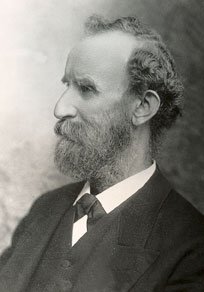

James B. Simmons

HSU Benefactor, Pastor

James Barlow Simmons was born to William and Clarissa (Roe) Simmons in 1827 in Dutchess County, New York, of Dutch and Scottish ancestry. When Simmons, the youngest of five children, was five months old, his mother was tragically thrown from a carriage and killed.

James Barlow Simmons was born to William and Clarissa (Roe) Simmons in 1827 in Dutchess County, New York, of Dutch and Scottish ancestry. When Simmons, the youngest of five children, was five months old, his mother was tragically thrown from a carriage and killed.

In his teens, Simmons spent three years at Madison University in Hamilton, New York, preparing for college. He entered the freshman class there in 1847, but soon moved to Brown University, living in a garret and doing janitorial work while attending school. He paid one dollar a month rent for his room and limited himself to no more than $1.12 weekly for food. He often ate only bread and milk, allowing himself the purchase of meat only twice a week. Simmons said of his self-inflicted frugality, “I had a bowl and fork, and would stick the fork in a piece of bread and dip it in the milk, withdrawing it quickly, lest it should absorb too much milk, for I had to be economical.” The bowl he used for meals is on display in the Richardson Library History Center.

Simmons graduated from Brown in 1851 and began three years of study in theology which culminated at Newton Theological Institution, near Boston. Also in 1851, he married Mary Eliza Stevens, a young Quaker, from Providence, Rhode Island. When her husband entered seminary, Mary also began to study Hebrew, Greek, and other subjects at the seminary. In 1854, Robert Stevens was born to them.

While Simmons studied at Newton, he acted as pastor of Third Baptist Church in Providence and quickly earned a fine reputation. In 1857, the young family moved to Indianapolis where Simmons took the pastorate at First Baptist Church until 1861 when they moved to Philadelphia to work in the Fifth Baptist Church. While there, he led the congregation in building a beautiful church in Gothic English style.

After he left Philadelphia, Simmons was awarded two honorary doctorates from universities which appreciated his ability in the ministry and his ability to motivate people to give funds to keep church schools open.

In 1867, he was appointed corresponding secretary of the American Baptist Home Mission Society. He confronted the condition of the four million slaves who were freed at the Civil War’s end who were living in poverty and needing education and other advantages.

His first effort as secretary was to establish a Christian school for freedmen in Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Southern Confederacy. In 1865, Simmons succeeded in obtaining for the Colver Institute an appropriation of $10,000 from the U. S. Freedmen’s Bureau, to purchase the old United States Hotel in Richmond as a relocation for Colver. Classes for the Colver Institute had been being held in a rented building known as Lumpkin’s Jail, which had been owned by a slave-dealer who had used it for holding and punishing slaves until they were put on the market for sale. The conversion of the hotel into a school, which was renamed the Richmond Institute in 1876, now gave these newly freed slaves a worthy location in which to obtain their educations. Richmond Institute was later incorporated into what is now Virginia Union University.

Following the Richmond endeavor, six similar schools were founded with the assistance of Secretary Simmons. Those include, Benedict Institute (now Benedict College) in Columbia, South Carolina; Leland University in New Orleans; Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina; Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C.; the Nashville Institute, now Roger Williams University, in Nashville, Tennessee; and Augusta Seminary in Augusta, Georgia.

In 1874, he retired from his position as secretary for the Mission Society to pastor Trinity Baptist Church in New York City for the next eight years. He was then elected as field secretary for the State of New York by the board of the American Baptist Publication Society. In this role, he spoke from dozens of pulpits to raise money for Bible and mission work. He had over the years involved himself in fund-raising campaigns for two others schools, one in Indiana which closed after a few years, and the other being what eventually became the University of Columbia in Washington D.C.

His reputation as a fund-raiser for higher education attracted the attention in 1890 of the trustees of the fledgling Abilene Baptist College. Funds had run out for the completion of the building, and upon the request of Dr. O. C. Pope, Dr. Simmons and his son came to Abilene to visit the proposed location of the school. Simmons saw a great potential in the fertile West Texas location with a field to draw from twice as large as the entire state of New York, and which was rapidly filling up with people. Rather than raise funds from other sources, Simmons gave from his own pocket. Over time, he and his wife and son, in addition to the $5,000 in cash originally given in 1890, gave to the school donations in excess of $20,000.

As a name for the school, Simmons chose Christlieb College, which translated from the German language is “College of Christ’s Love.” His wife and son, however, insisted upon making the school a monument to the educational labors of the Simmons family. An early building was named Anna Hall for Simmons’ granddaughter who taught art at Simmons College for a short time.

Mary Simmons passed away two years after the college opened and was the first to be buried on its grounds. James B. Simmons died December 17, 1905, at the age of 78. His remains were buried on the campus next to those of his wife. It was his desire that even their “very ashes may witness for Christian Education.”